I once lived in an apartment on a quiet street where my dog woke up annoyingly early for the first walk of the day. One summer, I noticed a young man regularly sleeping in his car on our street.

My morning dog walk often coincided with passing him as he brushed his teeth and put on his dress shirt and blazer. Then he’d drive away, presumably to work, where I would guess that no one knew he was living in his car.

Our society has a very narrow idea of what it looks like to be houseless, typified by mental illness and substance use, which massively fails to understand the nuances and complexity of the experience. These assumptions can also cause us to misinterpret the food needs of people who are not securely housed.

Houseless vs. Homeless

The words we use carry power, which is why it’s important to be thoughtful and reflective of our choices.

In my food pantry, we are intentional about using the term “houseless” rather than “homeless.” Because the term “home” encompasses a structure as well as our surrounding relationships and support system, “homeless” implies that someone doesn’t belong, both physically and socially. Although some of our clients lack a physical house, many have strong roots and relationships in the community that should not be dismissed or erased. This is their home, no matter where they live.

Our society tends to assume that people who are houseless only live on the street. The reality is there are many ways someone may be without a consistent place to stay.

- People who lack a physical house may jump from couch to couch in friends’ homes.

- They may live in a long-term hotel or a shelter.

- We serve an increasing number of people who are staying in their cars.

- Some individuals have a car which allows them to travel to a camp in the woods for greater privacy and safety.

- I’ve met individuals who rented a self-storage locker and lived there for months at a time.

Particularly in the Portland Metro area where housing costs are incredibly high, it’s entirely feasible that someone can have a steady income and a car but still not be able to meet the demands of a rental deposit and consistent bills. Without the capacity to prep or store food, it can be hard to access the food they need to thrive and be secure.

We often don’t know if people are houseless when they enter our pantry. When they don’t meet our visual expectations of an unhoused person, we often assume they are securely housed, which can influence the foods that are offered to them.

Accommodating Diverse Needs

The foods that food banks and pantries offer are generally not well-suited to those experiencing houselessness. Especially with the growing push for healthier, from-scratch options, food pantry resources increasingly require access to a kitchen and cooking implements.

Without consistent housing, our clients may not have a refrigerator to store food, a saucepan for cooking it, or even a fork to eat with which limits what these shoppers can eat.

Our food pantry is located downtown in a major metropolitan area with a significant houseless population. Years ago, the organization realized that there was a need for more options than fruits and vegetables and canned goods to meet the needs of the people who couldn’t use our average pantry offerings.

We now operate a Snack Window, which is open to everyone but particularly targeted at people without cooking capabilities. Here we serve donated sandwiches and salads from Safeway and 7-11, chips, granola bars, juices, protein shakes, and pastries from Starbucks. (Because it is all donated, we never know what we will get, which is why it is a “snack window” as opposed to a “meal” or “lunch” site).

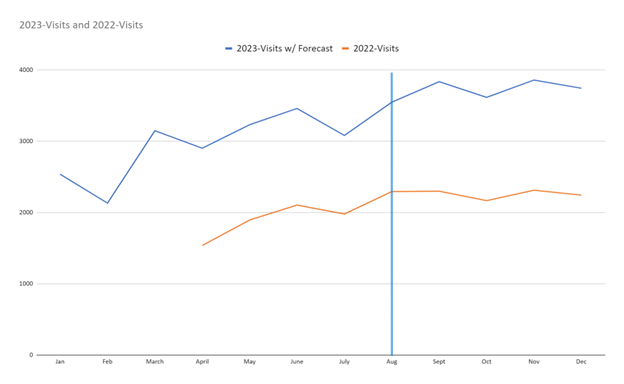

This window currently serves over one hundred individuals per day, including people living outside, in their cars, couch surfing, shelters, or in apartments that lack kitchens, cooking equipment, or utilities.

We also offer what we call a Traveler’s Box. I once received an impassioned note from a houseless client who was frustrated that when he had shopped at our pantry in preparation for a holiday closure, there were few options he was able to stock up on without access to a kitchen. This note inspired the Traveler’s Box for anyone who is looking for more than a snack but unable to cook.

These boxes include canned soups, fruit, meats (such as tuna and chicken) and meals like Chef Boyardee or Spaghetti-O’s, which are all pop-top and don’t require a can opener. We also pack shelf-stable milk and cereal, peanut butter, crackers, and snacks like chips and granola bars. Traveler’s Boxes provide more food than the daily snack window option but likely less than what people might take if they did a full shop, which is often ideal for those who may be on foot or have limited storage capacity.

The demand for these types of foods varies based on the population served. Food pantries in less accessible locations to individuals on foot may not have such a need for instant and easy-to-prepare options. But all anti-hunger organizations should assume that a portion of their clientele is under-housed, and ensure they offer options and services to support them.

How can pantries support people experiencing houselessness?

-Encourage donations of can openers, pop-top cans, and foods that don’t require preparation or refrigeration and make them easily accessible to clients.

-Seek out donations of prepared foods like sandwiches, cut fruit, and single-serve drinks.

-Educate volunteers, donors, and staff on the complexity of houselessness and discuss our assumptions and stereotypes.

-Engage or partner with local shelters who may offer or know of additional resources.

The opinions expressed here are solely my own and do not express the views or opinions of my employer.

Want to learn more about food justice? Subscribe so you never miss a post!