I once met a food pantry volunteer who told me that at their pantry, they checked the quality of donations of milk by opening one container and drinking it. If it tasted okay, the donation was put through.

There are a million things wrong with this strategy. The one I can’t get over is that pantries rarely get large donations of the same product, which means that you can’t assume it all has the same expiration date or even comes from the same source. Tasting one carton tells you nothing useful, and I can’t figure out how this would ever be considered an appropriate strategy.

Many food pantries depend on donations from stores that are made because products are at or past their expiration date. This means that we carry the burden of ensuring all the food we distribute is safe to consume.

It’s important to remember that many people experiencing food insecurity also lack access to affordable healthcare, which means getting sick from food pantry food could be catastrophic.

Besides offering real health risks, distributing unsafe food demonstrates a profound disrespect for the people we are supposed to be uplifting. The responsibility is not one to be taken lightly.

The challenge is that few pantries have enough food to serve their community, which increases the temptation to distribute questionable items.

While there are clear requirements about how to manage food safety in donation programs, food pantries also don’t always have the infrastructure or training necessary to maintain it.

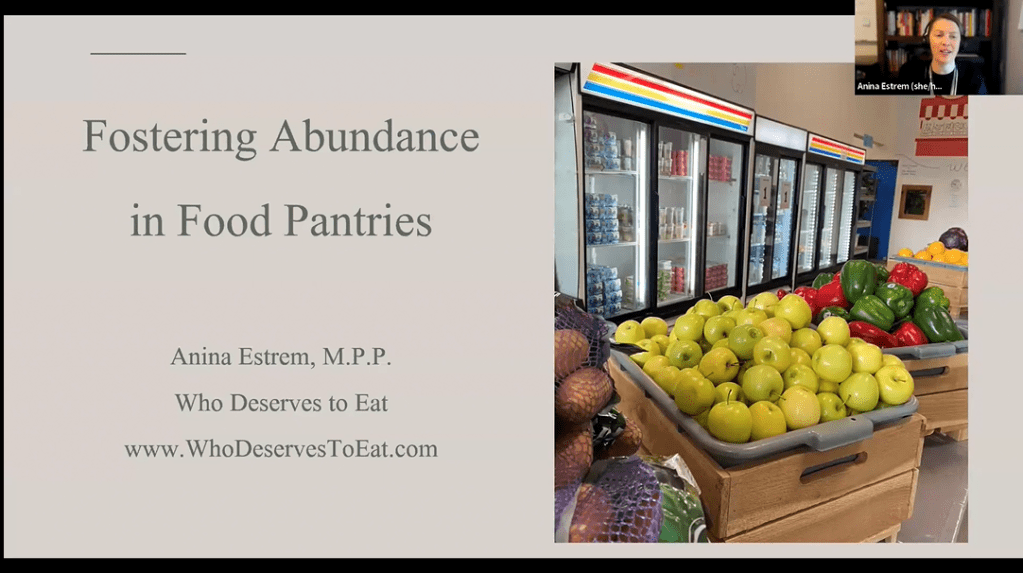

At one of the first food pantries I worked at, our refrigeration was limited to three regular sized refrigerators while regularly serving over 100 households. I spent many winter days with the warehouse door open to chill the items that didn’t fit in the fridges. This is not how this should be done, but illustrates the impossible situation we put food justice organizations in.

It’s important to appreciate just how hard it is for food pantries to maintain food quality while depending on inadequate infrastructure, insufficient resources, and an absence of training.

This is why food safety training needs to be an ongoing priority for all staff and volunteers.

Volunteers often do not receive adequate food safety training because staff may not have the time or the knowledge themselves. Many volunteers come to food pantries with a primary goal of reducing food waste– which often translates into trying to distribute as much as possible and discarding as little as they can. An unintentional consequence of this goal is that they may distribute foods that are no longer safe to consume.

How food pantries can foster food safety:

- Train your partners! Ideally, regional food banks have resources for illustrating food safety expectations to donors. Explore ways that you can provide feedback to these donors- most genuinely want to help and not add to your burden, so let them know what donations are or are not acceptable.

- Don’t be afraid to say no to a donation you don’t think is safe. I once had a manager with a fear of confrontation, which means my team found ourselves regularly throwing out unsafe donations so that we didn’t risk offending the donor. This is a waste of time, energy, and resources. If a donor is only giving you garbage, there’s no value in the relationship anyways.

- Host regular food safety trainings for your volunteers. When I worked at a regional food bank, we had a volunteer shift sorting fresh donations that included a ten minute orientation on food safety standards that we shared with every single shift. It was boring and repetitive, but also essential for keeping our food supply safe and helping volunteers become better-informed consumers. Normalize sharing it so often that your regular volunteers can recite along with you. They’ll be more likely to help teach new volunteers and maintain appropriate standards.

- Empower your staff to take more advanced food safety training courses than just getting their food handlers card. Consider what other advanced certifications are out there, and see what options there are to take regular or ongoing trainings, instead of just when their cards expire.

- Don’t be afraid to advertise your infrastructure needs. Encourage donors to contribute to your refrigerator fund or help with the purchase of a three-compartment sink instead of the food purchasing fund. Brainstorm ways that you can navigate the space and resources available to help your team be more effective based on the types of donations that you regularly receive, or that you’re trying to get more of.

The opinions expressed here are solely my own and do not express the views or opinions of my employer.

Want to learn more about food justice? Subscribe so you never miss a post!