Hunger is an emotional subject. Any human who feels compassion and empathy should feel discomfort at the idea of another person going hungry. Unfortunately, the passion it carries also results in the development of policies fueled by this emotion rather than data and evidence.

American society has internalized assumptions about who is hungry and who deserves assistance, and too often these biases result in weak or ineffective policies that respond to feelings rather than reality. We see this prioritization of emotion over data at all levels, from local to federal policy.

Food pantries implement limits on food items so that no one can take too much, based on the assumption that people are greedy, selfish, and don’t know their own needs best. SNAP benefits have work requirements, reflecting the idea that people living in poverty are lazy and won’t work unless forced to. Anti-hunger resources for seniors and children far outweigh those for working adults, based on the idea that some populations have the power to extricate themselves from hunger while others are helpless against it.

These policies tell us far more about our own assumptions than they address the reality of the problem.

Although food banks and anti-hunger organizations are growing increasingly sophisticated in their advocacy efforts and focus on the root causes of hunger, and can utilize data to back it up, not all organizations have the capacity or access to the same level of expertise.

Food pantries often lack staff or volunteers with experience working with data, which means even if they collect relevant information, they may not fully understand what it means or how to use it to advance their efforts.

This is a huge opportunity lost, because as the implementers of on-the-ground anti-hunger efforts, food pantries have some of the greatest opportunities to influence how well their community eats.

As recipients of both federal and state funding and other donated resources, food pantries are obligated to collect a certain amount of information from the people they serve, including age, declarations that they meet income eligibility requirements, as well as recording how much food they distribute. Additional information collected varies based on country or state, coalition membership, and the pantry’s own interest in data.

Here are three things food pantries can prove immediately with the data they already collect:

Hunger rates are predictable.

Every year, our pantry sees a significant increase in clients from September through December. Without fail, the summer slump ends the moment school starts, peaks in November before Thanksgiving, and finally begins to slow down mid-January. Anti-hunger organizations should not be surprised to see these fluctuations throughout the year, and should plan accordingly. Rising inflation clearly correlates this year with increasing food insecurity. We have no excuse to be surprised by the increasing need, yet too many organizations are shocked and overwhelmed at the demand every holiday season.

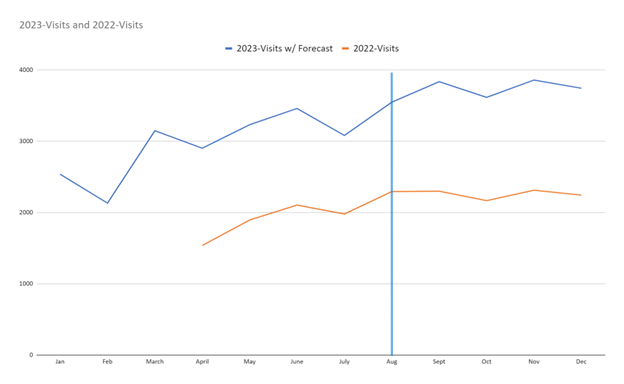

This graph shows my pantry’s total client visits since April, 2022 (when we reopened as a grocery-style model). The jump in March, 2023, is due to the expiration of pandemic-era SNAP benefits. Using past trends, this graph makes predictions for the numbers we’ll receive this winter. (I’ll keep you updated on how accurately this plays out!)

Food pantry clients work.

Most food pantry households have at least one member who is employed. Although our society is eager to assume that people utilizing welfare seek to exploit the system, the employment status of pantry clients proves otherwise. Food pantry clients are eager for work, but they regularly struggle to access well-paying jobs (as non-food pantry clients also must recognize). Surveys and anecdotal evidence can quickly disprove the myth that people use food pantries to avoid employment.

People don’t take food they don’t need.

Everyone knows what foods they need to thrive. Recognizing this, there is increasing popularity in the grocery-style food pantry model, which allows clients to select the items they want rather than receive a prepacked selection. The implementation of this system has demonstrated that shoppers know what foods they will and will not use. Clients rarely take everything that is offered because they don’t want to take what they won’t use, contrary to popular assumptions. Assessing what foods people take and in what amounts provides ample evidence that clients know their own needs best and are not taking food they won’t eat.

This is only a short list of the assumptions that food pantries can dispel through data. With a commitment to evidence and interest in continuing education on the part of leadership, food pantries can use the information they already have to create effective, powerful policies that empower their shoppers rather than play out their biases.

The only way that we can effectively reduce hunger in our communities is through the development of policies that are based on reality rather than the assumptions in our gut.

The opinions expressed here are solely my own and do not express the views or opinions of my employer.

Want to learn more about food justice? Subscribe so you never miss a post!

2 thoughts on “Don’t Let Your Heart Write Anti-Hunger Policy”