“Just think positive!”

Who hasn’t had someone tell them that thinking a certain way will influence the outcome of a situation? Although it is rarely welcome advice and easier said than done, there is validity to the idea that how we think about problems influences our understanding and capacity to solve them.

There is nowhere this is more true than in the effort to end hunger. The more I learn, the more convinced I am that successfully ending hunger must start with changing how we think about and discuss it.

There is so much baggage and emotion tied up with our society’s existing understanding of hunger that building a new framework will be easier and more effective than trying to rework the old one.

Changing the language we use is a small step that should be followed by more tangible action, but is an incredibly powerful way to bring more food justice to the world around you.

Here are three examples of how word choice impacts hunger:

Food Stamps vs. SNAP Benefits

From 1939-2008, people using government food assistance relied on Food Stamps. Highly visible pieces of paper made it hard to use discreetly, and cultural biases and assumptions led to stigma against the people utilizing this essential resource. Because of this, Food Stamps were deliberately renamed the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, in 2008. Although SNAP is a term slow to be adopted by the general public, the change was a intentional effort to reduce the stigma of food assistance. Given that embarrassment for needing help is one of the primary barriers to utilization, this is a small but important effort towards making food assistance feel more accessible to everyone.

Food Bank vs. Food Pantry

When I worked at a large urban food bank, people regularly came to us for food. These visitors were given a small box of nonperishable foods, and a resource list of local food pantries that would be able to provide them with more help. The formal distinction between a food pantry and food bank isn’t widely known, which often left these individuals feeling embarrassed and or even angry when told we didn’t offer the assistance they were looking for.

Food banks are food hubs that collect and store food, which is then distributed to partner agencies such as food pantries or soup kitchens. Although the terms are often used interchangeably, people looking for free groceries are looking for a food pantry. Before the pandemic, few food banks distributed food directly to people experiencing hunger (although since 2020 the number who manage some type of distribution has grown significantly).

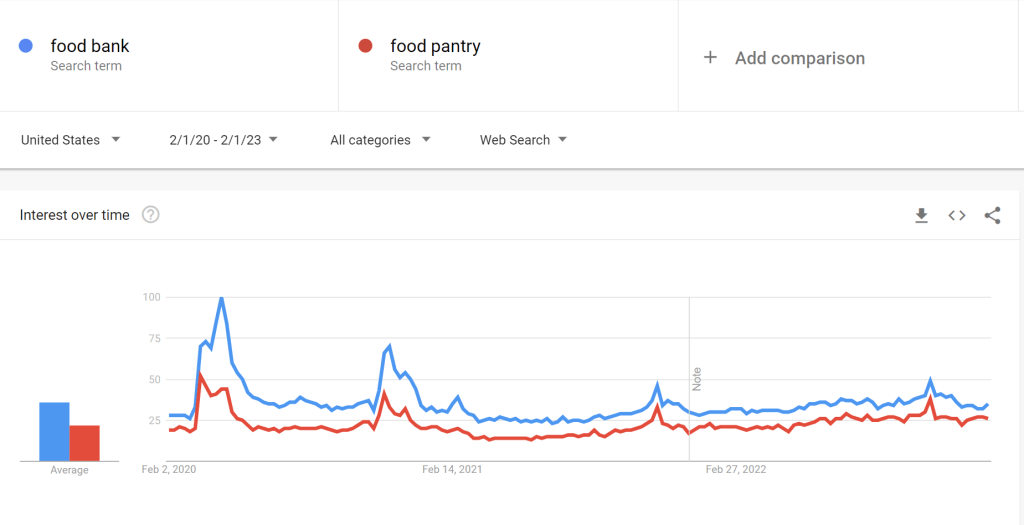

Data clearly shows that people seeking food assistance are more likely to use the search term “food bank” rather than “food pantry” as they research options. Although I am generally an obedient rule-follower, food pantries adopting the title of food bank would help ensure that people in need find them more easily and avoid awkward encounters at food banks.

It may be time to think of a new term for food banks that more adequately encompasses the work they do, especially as many expand their missions to include advocacy, education, and services beyond that of a food hub.

Free School Lunch vs. Universal School Meals

Framing has a huge impact on how our ideas are perceived. Particularly in America, there’s a staunch expectation that people need to earn their success, and strong opposition to the concept that anyone should be given anything for free.

One way this idea manifests is in the current discourse around school meals. There is a growing movement to offer free meals to all students in low-income public schools and not just those who qualify. Requiring an application and examination of a family’s income stops many families from applying, which leaves their children without access to school lunch.

(I once worked reviewing these applications for CACFP, the school lunch equivalent for daycare centers, to ensure that students qualified for a free or reduced-price meal program. It was clear that language barriers, education level, and understanding of the program were major factors influencing who applied, and that the number of applications didn’t reflect the true needs of the community.)

Advocates are working to ensure that high-poverty schools offer meals to all students to eliminate the bureaucratic barriers that leave kids hungry. While much of the political pushback focuses on the costs, there certainly remains an aura of reluctance to provide anything for free.

If we choose to advocate for universal school meals rather than free lunches, it reduces the fear that anyone receives anything for free (that we think they might not deserve). It’s hard to argue that children don’t need lunch at school, so simply renaming this policy helps make it palatable to people with more diverse perspectives.

The words we choose to talk about hunger have a powerful impact on how we, and the people around us, think about the issue. Anti-hunger advocacy doesn’t have to be phone banking, or volunteering, or lobbying for policy change. Carefully considering the words we use offers an opportunity to implement subtle shifts in how our community thinks about hunger, which will help us foster buy-in when we do choose to be more active participants.

The opinions expressed here are solely my own and do not express the views or opinions of my employer.

Want to learn more about food justice? Subscribe so you never miss a post!